[ July 2 - July 31, 2004 ]

Our most recent trip to Iran was quite unusual in several respects. Firstly, we spent most of July in the country which is quite late in the season. The scorching heat of the daytime when temperatures hardly ever dropped below 40 °C was not a good time to do much serious field work but as there are hardly any heliophilic species around at this time of the year it didn't matter.

On the other hand at night when the temperatures dropped to a "comfortable" 30 °C the arid areas were teeming with life. Sleeping in air conditioned hotels during the day-time, getting up in the late afternoon and setting up our light trap shortly before dusk was how we adapted to these difficult conditions. When the light trap was set up (Figures 1 to 3) there remained little else to do but wait for the night, and especially for the short period of time right after dusk, "the magical half an hour" when most of the interesting nocturnal species used to come to the light.

Figures 1 - 3 [Photo © M.Rejzek] Light trap |

It was our intention to record Iranian Prioninae. These insects are invariably nocturnal. Shortly after dusk many species of this tribe fly around in search for the opposite sex or for substrates convenient for oviposition. The flying beetles use the moonlight for navigation. Occasionally they get confused by strong sources of artificial light and fly to them. This works especially well when the moon is new or obscured by clouds.

"The magical half an hour" is therefore the most likely time period for attracting species of genera such as Pogonarthron, Mesoprionus or Monocladum. In many cases females never come to light.

Later at night truly nocturnal species such as Anthracocentrus rugiceps (Gahan), or Prinobius myardi Mulsant and many species belonging to tribes other than Prioninae such as Xenopachys matthiesseni (Reitter), Cerambyx spp. or Derolus iranensis Pic came to our light trap.

Most dusk-active species fly again shortly before dawn. It is also worth mentioning that there are plenty of nocturnal species that never come to light. Recording these species requires a focused search of their hosts aided by a good torch.

As in other countries of the West-Palaearctic Region there are fewer late-summer Cerambycidae species in Iran than species occurring in the spring and early summer. Most of them are, however, rare and conspicuous and it is therefore perhaps no surprise that our group set ourselves the task of recording them and learning more about their biology and habitat requirements. This idea was greatly supported by Michael, a member of our team who specialises in the subfamily Prioninae. For his body size Michael is not an easy-to-overlook member of our team (a brilliant cook by the way). Amongst our group it is commonly believed that Michael prefers Prioninae simply because he can see them better than, for example, a tiny Phytoecia.

It was our plan to travel south along the Zagros Mountain Range down to the Persian Gulf and from there to go to the eastern mountain ranges bordering the Central Persian desert plain or more specifically the Dasht-e Loot desert (دشت لوت).

Before we could start the field work we had to get there however. Driving in Iran is always quite a challenge. Not so much because of the roads as they are generally very good and even signposting is reasonably good and instructive. By "reasonably" I mean that local names in Farsi are frequently accompanied by an English transcript. As a rule this transcript is, however, different to what you can read on your map and so a good deal of imagination is required to get around. Another challenge is presented by cities "with more than one name". Jiroft (جيرفت,), for example, is a lovely modern city in the south of Iran, that in our maps was confusingly called Sabzāwārān. In a few instances the signposting gave one name when we entered the city and a different one on leaving. The only real problem was, however, presented by signposts in large cities. Highways in large cities such as Tehran do not show directions to other places but rather the name of the highway. This of course leads to massive confusion.

By far the greatest challenge however is sharing the roads with Iranian drivers. It seems that there are no specific rules observed except: if you hit my car from behind it is your fault. If you wish to get anywhere in this large country you have to adapt. So, for instance, driving twice the speed limit and overtaking in dangerous situations had to become our daily routine. Iranian police are frequent on the roads and they even stopped us a couple of times for breaking the speed limit. With a polite smile on their faces, so typical for all the people of this country, they told us off and let us go without any further consequences. In a similar situation in my own country the policemen would very likely frown and definitely charge me a fortune. A very generous, polite and pleasantly reserved attitude to foreigners is typical in Iran. This generosity extends so far that on several occasions when we stopped at garages to have some minor fault repaired the staff refused to take any money from us. Quite impressive indeed.

Hotels are easy to find in Iran and they are of good quality. As for the price do not be surprised when you are asked to pay USD 100 a person per night. If you say politely: "Would 10 dollars do?" the deal is almost always struck. If you are unlucky you will end up paying 15.

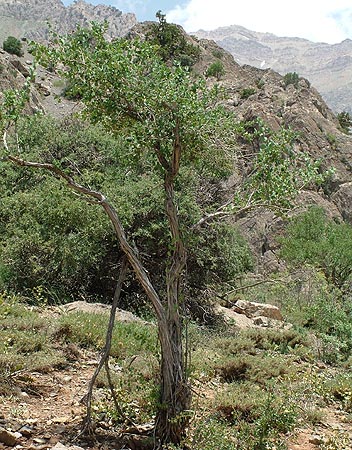

Our travelling began in the north of the country, in the foothills of the northern Zagros. Zoogeographically this area belongs to the Irano-Turanian region, a subregion of the Palaeartics, mainly resembling Eastern Anatolia. High altitudes and a strongly continental climate support hardly any higher vegetation. The flora is restricted to herbaceous plants and a few shrub species comprising Ephedra, Berberis but most of all a variety of Astragalus spp. In this region Astragalus serves as host for Xylotrechus ilamensis Holzschuh. The species shows tiny but sufficiently constant differences to Xylotrechus sieversi Ganglbauer, a species with a much wider distribution range. In the beginning of July Xylotrechus ilamensis was frequent in the host as praepupae, pupae or adults in pupal cells. The species is strongly gregarious and so in one dead branch several dozens of individuals could sometimes be recorded. In Zagros the species' range extends from the north to the south. In Ilam (ايلام; the type locality) we collected a number of specimens (topotypes) showing no significant differences to populations collected elsewhere in the mountain range. Vadonia bittisiensis Chevrolat was another interesting species recorded in the vast steppes of the northern Zagros.

Travelling south to the central Zagros we reached a significantly species richer region characterised by the presence of Quercus brantii. This subregion (also referred to as the Zagros Mountains forest-steppe) stretches from south-eastern Turkey and northern Iraq to the western edges of the Zagros Mountains. Mountainous regions surrounding the Mesopotamian Lowlands manage to capture the sporadic precipitation. As a result a narrow band of relatively rich vegetation accompanied by a number of characteristic insects has developed here. In the north-west of Iran Quercus brantii is frequently accompanied by Q. infectoria, Q. boissieri and Q. libanii. Very nice examples of this subregion are present in Ilam (province Ilam, Figures 4 to 10) or in Dorud (province Lorestan). Here we recorded Plagionotus (Echinocerus) floralis (Pallas), Chlorophorus varius damascenus (Chevrolat), Stictoleptura (Stictoleptura) tripartita (Heyden, 1889), Osphranteria coerulescens inaurata Holzschuh and a Stenurella species which is very likely new for science. Night collecting revealed Cerambyx (Cerambyx) cerdo Linnaeus, Prinobius myardi Mulsant, Xenopachys matthiesseni (Reitter) (this species extends as far north as Ilam!), Mesoprionus persicus (Redtenbacher) (both males and females) and Derolus iranensis Pic. Moreover during the day we collected larvae of a Purpuricenus species currently being described from the Zagros Mountains.

Figures 4 - 10 [Photo © M.Rejzek] West Iran, province Ilam, the surroundings of Ilam |

Further to the south the Zagros Mountains forest-steppe becomes richer in vegetation comprising an amazing variety of shrub and tree species such as Crataegus azarolus, Acer monspessulanum ssp. cinerascens, Pistacia khinjuk, Pyrus syriaca or Amygdalus. In higher altitudes Pistacio-Almond scrub has often developed consisting of shrubby species belonging to the genera Pistacia (P. atlantica, P. khinjuk and P. vera) and Amygdalus (A. scoparia, A. haussknechtii, A. elaeagnifolia, A. eburnea, A. lycioides and A. kotschyi). Other shrubby species are Cerasus microcarpa, Acer monspessulanum ssp. persicum and ssp. cinerascens, Daphne angustifolia, Rosa spp., Berberis integerrima, Colutea spp., Cotoneaster spp. or Crataegus spp. The finest examples of these habitats can be seen in the surroundings of Shiraaz (province Fars, Figures 11 to 18). Here during the day we recorded the already mentioned Purpuricenus species new for science, the nominate Osphranteria coerulescens coerulescens Redtenbacher, 1850, Oberea (Amaurostoma) erythrocephala erythrocephala (Schrank), Chlorophorus adelii Holzschuh (larvae) and at night, Mesoprionus persicus (Redtenbacher), Cerambyx (Cerambyx) cerdo Linnaeus, Xenopachys matthiesseni (Reitter), an Apatophysis sp. that still remains to be determined.

Figures 11 - 18 [Photo © M.Rejzek] SW Iran, province Fars and Buyer Ahmad-o-Kuhgiluye, the surroundings of Shiraaz |

Leaving the mountains around Shiraaz and heading south the Irano-Turanian region abruptly breaks into a completely different world: the Saharo-Sindian (or Nubo-Sindian according to some authors) Region. In Iran this region (also referred to as the South Iran Nubo-Sindian desert and semi-desert) is restricted to the lowlands surrounding the Persian Gulf and is characterised by exotic plants such as Acacia, Prosopis, Ziziphus, Calotropis or Phoenix dactylifera (Figures 19 to 25). Strictly speaking this area of course does not belong to the Palaearctic Region any more. For practical reasons however, we decided to include this stunningly beautiful area in our systematic research. The scorching heat of the daytime did not seem to be tolerated by any sort of beetles at all and so we happily gave up on any activity and slept all day in a comfortable air-conditioned hotel. At dusk, however, when the bats began to creep out of their hideaways, our group of lunatics started to stir as well. Once the temperature dropped to 40 °C we dared to leave the hotel. Under 40 °C human existence slowly became possible. It still ,however, presented significant challenges to the integrity of our plastic cigarette lighters which kept exploding in the heat. Actually, a lighter exploding in a shirt pocket emitted vapourising liquid which was a pleasantly cooling experience, albeit very short lived.

Figures 19 - 25 [Photo © M.Rejzek] South Iran, province Hormozgan, the surroundings of Bandar-e Abbas |

Sticking your head out of a window whilst travelling by car felt very similar to how you would imagine putting ones head into a fan oven on full power to be. All these pleasures were magnified by the omnipresent Phlebotomid sand fly transmitting Leishmania, scorpions, the rare but still present Iranian desert cobra and the very frequent Saw-scaled Viper (Echis carinatus), a fatally poisonous snake. This little fellow effectively mimics the colour of the soil and even worse it seems to be too lazy to move away when you are about to step on it. Poking the snakes with a branch and making a lot of noise only resulted in the snake coiling itself up and assuming an attack position. To make things even worse, the snakes systematically gathered in the vicinity of dead trees perhaps looking for the same reasons as us - the insects. To overcome this peril I felt it necessary, equipped with a head torch and another torch held in my hand, to walk around in the high grass in a way that closely resembled John Cleese' Ministry of Funny Walks. All this hassle and much effort was eventually rewarded by one of the most spectacular entomological experiences, the finding of living Anthracocentrus rugiceps (Gahan). The females of this insect almost resemble a small rabbit in size and only just manage to walk around. The significantly smaller males climb trees but I believe only just so. The females are very crepuscular and so we managed to find just two specimens. The males apparently spend more time loitering around and so we stumbled across more of them. In the lowlands of southern Iran we also recorded Osphranteria sauveolens Redtenbacher, Zoodes compressus (Fabricius), Iranobrium davatchii Villiers, Niphona (Niphona) indica Breuning and Cerambyx cerdo iraniensis Heyrovský, all very exciting species.

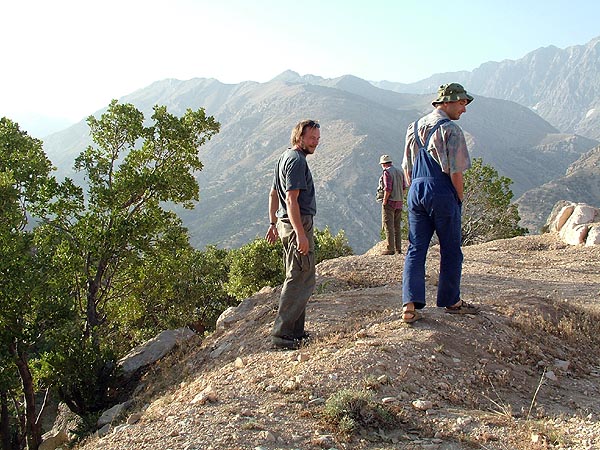

From the Persian Gulf we headed north-east and visited mountain ranges bordering the Central Persian desert basins, the Dast-e Lut desert. After travelling for hours in the incredible heat the Gebal Barez mountains rose abruptly from the plateau. We found an excellent hotel in the foothills of these mountains. When observed from the hotel windows the mountains looked extremely barren. In the evening when most of us dared to get up and drive in that direction we first saw completely barren rock. After a while, however, and with increasing altitude the countryside gradually started to change and we saw the first signs of life, although very modest ones. At an altitude of about 1000 m sparse shrub communities started to appear and even higher in altitudes above 1500 m we started seeing Pistacia trees! At 2000 m the sparse trees became denser and formed a forest-like community: a Pistacia forest, perhaps better referred to as a forest-steppe (Figures 26 to 32). This habitat which was dominated by Pistacia atlantica and P. khinjuk also supports almond (Amygdalus spp.), Pteropyrum spp., Lycium spp. and others. The Pistacia forests are typical for these mountains and can only be found in Iran and neighbouring regions of western Pakistan. In the Gebal Barez mountains we recorded Monocladum iranicum Villiers (both males and females), a species endemic to Iran, larvae of some Agapanthia species, the recently described Calchaenesthes pistacivora Holzschuh and larval galleries of Mesoprionus petrovitzi (Holzschuh). Although we tried very hard we did not manage to find any adults of the last species.

Figures 26 - 32 [Photo © M.Rejzek] South Iran, province Kerman, the Gebal Barez Mountains |